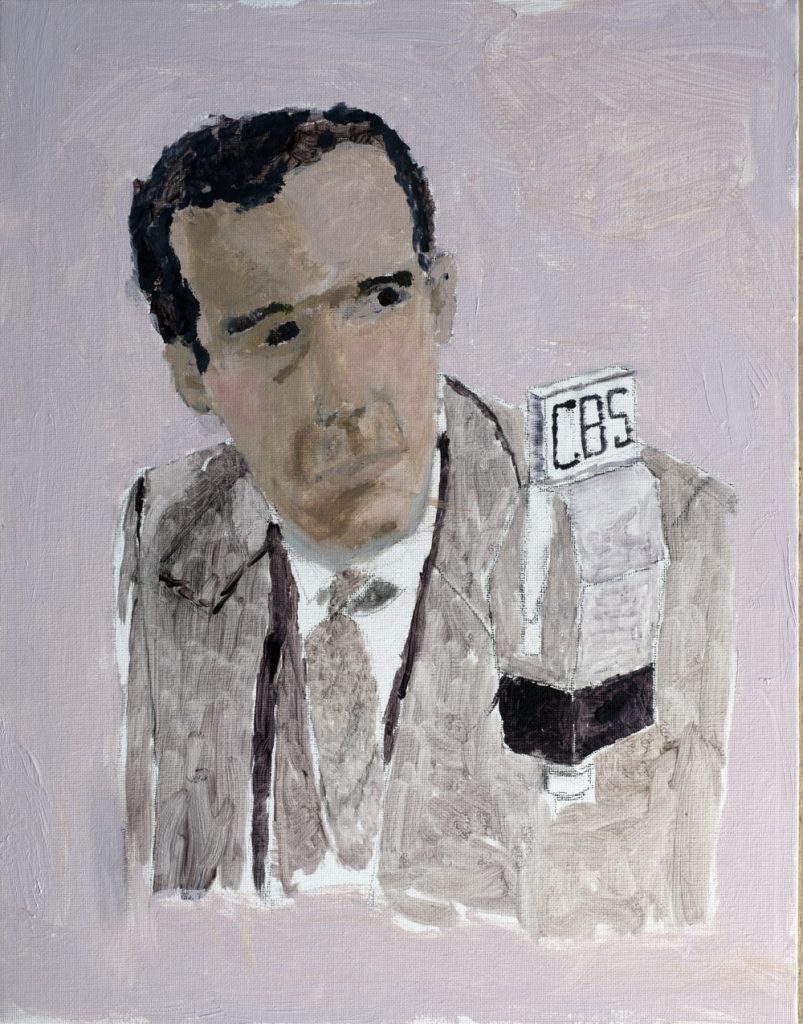

I painted a portrait.

Once upon a time, before American journalism reached the current state of terminal degeneration, and yet, paradoxically, before the Best and the Brightest piled into it (now replaced by Dumb and Dumber), there was a man who is credited with the creation of broadcast journalism. His name was Edward R. Murrow, and may it not be erased by the sands of time.

Five things you need to know (this is a popular news site hook) for your new day:

- traffic report

- rain?

- how much gas is in your tank

- your credit card balance

- the location of your wallet and keys

Since all this is readily gained without much help from the media (unless you are habituated to the weatherperson wearing an oversize tie), a large proportion of the news is now entertainment, mainly schadenfreude.

But there was a time before that, before a major news site hired a comic book writer to critique the F-35 fighter, before another major news site ran Russian propaganda as opinion, before the word “were” became equivalent to “where”, before the current intermingling of fact, opinion, and fiction. It was a time before it became style to couch every important issue as a rhetorical question, as in “Is ISIS a threat to the U.S.?”

Even the NY Times is not immune. Recently, an article discussed computer security for the traveler. Ignoring the considerable human resources of the Times in the area of IT, outside credentialed experts were consulted. The article failed to mention VPNs, proffering instead valueless advice couched in lame aphorisms.

In the time before, we had the Walters, Lipmann and Cronkite, whose interpretations were always conceived and given with the solemnity of great duty. But in broadcast journalism, Murrow was first. He is described as not having been a genius, but with an uncanny ability to recognize talent. All the things he did prior to March 9, 1954, were enough to describe an illustrious career. But on that night, his show See it Now assured Murrow’s place in the pantheon of heroes.

There was then a Senator of Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, whose histrionic political posturing involved the destruction of professional lives by a kind of inquisition against communist moles in government and media. Grass-roots support required a continual stream of innocent victims, who were required to name names to save themselves from the black list. Fueled by memories of the Red Scare, and the undeniable presence of some communist sympathizers, McCarthy’s bonfires roared on. Even Ike seemed reluctant to take him on, hoping, perhaps, that McCarthyism would burn itself out.

On March 9th, Murrow took on McCarty with an expose that would eventually lead to the Army-McCarthy hearings. At risk was Murrow’s professional life, for no potential victim was free from the threat of fabricated evidence and innuendo. Murrow did not invent muckraking, but he refreshed the tradition, and did so at great personal risk. Characteristically, he resigned from CBS on a matter of principle in 1961.

But three years before that, in 1958, Murrow, in his “Wires and Lights in a Box” speech, decried the shift of broadcast news away from information, towards entertainment. Gradually, the prestige that accrues to those who tell important truth has yielded to the profit motive. Fifty four years after Murrow quit CBS, Brian Williams was suspended from NBC News on a matter of shame. In six months, he will be back. In what capacity should a morally compromised person associate with broadcast news? And why should we believe him?

Perhaps Williams’ error was not caused by a sense of personal grandiosity, but an attempt to score in the ratings war, casting himself not as the intermediary, but the participant, in combat operations. For the marketers who have made the public taste into a science discovered that, aside from schadenfreude, the public has an appetite for sensual, vicarious experience. (During World War II, Murrow flew on 24 combat missions, when loss rates varied between 5 and 16 percent. His motives are not in question.)

Video is overtaking text. This began long ago, when folks lined up in front of the TV, to watch someone take 15 minutes (+ commercials) to read off a teleprompter what a reasonably intelligent person could read in 3. This comes of cultural habit. We seem to think that the face and voice of the speaker tell us something his words do not. With Murrow, the supposition held. With Brian Williams, it did not.

So instead of getting at the facts, we are offered entertainment by videos of the destruction of terror, terrible accidents, or anything involving massive loss of lives. But the workings of these infernal machines are all very much alike, their gruesome grandeur meaningless. By catering to the public appetite for circus, so much remains unsaid.

If you’re not into barrel bomb havoc, you can take a trip with a CNN reporter on an air boat on Lake Chad, in search of Boko Haram. We’re given a glimpse of a sandy shoreline, and told that it’s too dangerous to continue the chase. While the reporter’s caution is laudable (who needs another hostage!), it’s of interest comparable to the other favorite, “Strange Sea Creature Washes Up on Beach.” Take a few seconds. How many questions come to mind about Boko Haram? How do they live? Who do they talk to? What do they say?

The circus may be the daily dose of schadenfreude, or the vicarious thrill of a joust with danger, but it does not inform the citizen. Murrow saw this coming. He had an argument with William S. Paley, president of CBS, whose history in broadcast resembles Randolph Hearst’s in print. Paley was a great womanizer, but left a legacy of endowments and buildings named in his honor, which may not clear his ledger.

For an icon of sterling quality, images of Murrow are surprisingly unavailable. Web images are mere thumbnails, larger images restricted by Tufts University, holder of the Murrow archives. I thought the world needs to see an honest face once in a while. My portrait of Murrow was inspired by a number of low resolution images, but is a copy of none of them, and therefore free of copyright restriction.

Initially, I worked from black-and-white photos. Later, I found some color photos that give Murrow an improbably rosy complexion. Murrow smoked upwards of 60 cigarettes a day. If you know what Murrow looked like, sans TV makeup, your comment is requested. The painting is not finished, and it may never be. I might paint his tie red, but don’t wait for it.

The portrait is free to use by liberals of all persuasions. There is, of course, the possibility it will appear in an article titled, “Edward R. Murrow Would have Approved of Fracking: Here’s Why.” But I think the risk is worth the reward. Many potential uses exist. Printed at Wal-Mart in suitable sizes, here are some ideas:

- NBC employees could be required to carry it as a wallet card, the reverse side of which would contain the statement, “I am a good boy”, signed by the employee. Larger portraits could adorn their office walls. If desired, I can work the painting to give Murrow a glowering, threatening countenance.

- Circus Nuevo Nuevo news teams could be required to stare at it, while observing a moment of silence, before they set off to video their next vicarious thrill.

- Reuters could use it to help their employees to understand that being better than RT (Russia Today) is not good enough.

- The NY Times could hang it on the wall, with grappling ropes attached, to halt their slide.

But if you will pardon my audacity, please use the jpg in any way that a glimpse of an honest, fearless, and literate man might buck you up.

And me? I’m thinking of forging Murrow’s signature, with the line, “[My dad’s name] we had good times in the war…Ed”, and hanging it in the kitchen. I never said I was perfect.

If you want to be nice, please credit, “Use courtesy of Number9.”